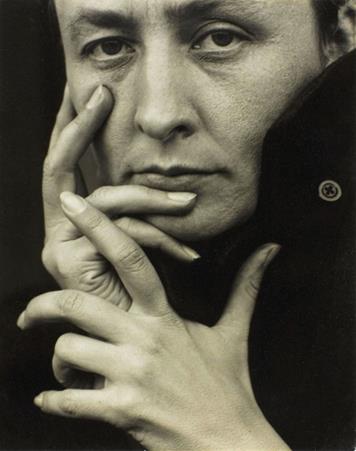

Georgia O’Keeffe was born to dairy farmers in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, in 1887. She already wanted to be an artist when she was ten years old, taking lessons along with two sisters. After high school in Virginia, she studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), where she was at the top of her class, and the Art Students League in New York, where she won awards and a scholarship. When her family could no longer afford art school, she worked as an illustrator, then had several teaching jobs, the last heading the art department at a college in Canyon, Texas, that is now part of the Texas A&M system. During those years, she experimented with charcoal abstractions. In 1916, a friend took them to Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 gallery. Stieglitz, a prominent photographer and art dealer in New York, was so impressed that he showed the drawings in his gallery.

O’Keeffe also painted watercolor landscapes, capturing her feelings as she took in the vistas, more than simply recording what they looked like. She was very anxious about World War I, especially since her brother was sent to fight in France. She questioned participation in the war and advocated her position from the college to local stores. As she recovered from the flu of the 1918 pandemic, she felt she had to paint The Flag.

The stars and stripes are taken over by blood red. Because anti-war positions were illegal under the new Espionage Act of 1917, the painting was not publicly displayed until 1968. When you look at the watercolor, do you think it presented a danger to the country?

Stieglitz urged O’Keeffe to move to New York City in 1918 to devote herself to art. He promoted her work and supported her with living expenses and places for her to live and paint. He also convinced her to drop watercolors, believing they would brand her as an amateur female artist. He photographed her hundreds of times, often in the nude, and exhibited that work. In spite of Stieglitz being twenty-four years older, they fell in love and married in 1924, when he divorced his first wife. He began an affair in 1928 with Dorothy Norman, a social activist/arts patron turned photographer/writer.

Even before moving to New York, O’Keeffe painted flowers and other objects from nature. But she addressed other subjects as well. In Blue and Green Music, she described music visually, with shapes and colors, a good example of synesthesia.

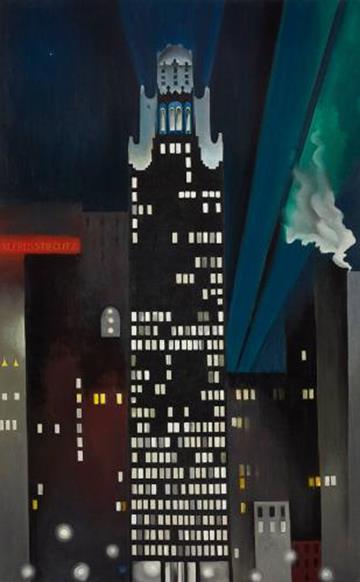

O’Keeffe got to know many avant-garde artists through Stieglitz and the gallery. With paintings of skyscrapers, she participated in America’s first modern art movement, Precisionism, which celebrated American modernity.

By that time, she herself was recognized as a prominent American artist for her skyscrapers and flowers. She had her first retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum in 1927.

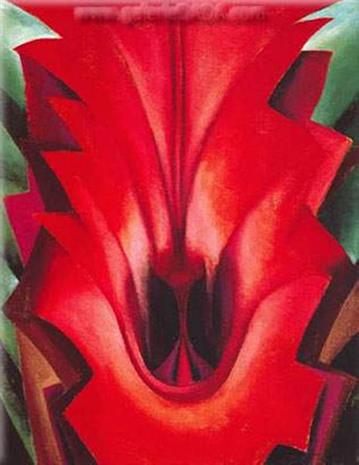

O’Keeffe painted flowers since 1915, producing more than 200 such paintings over her lifetime. For example, she featured red canna lilies in at least nine paintings. Looking at a watercolor from 1915, we see a stalk of about five flowers painted in a traditional way. In a 1919 oil, she focuses on just one lily against a background of saturated green, yellow, and blue. In Inside Red Canna from the same year, she loses the background and takes us into the flower. Seeing these three paintings together is like using a zoom lens.

Many viewers believe O’Keeffe’s close-ups of flowers represent female anatomy. She denied that, but many people don’t believe her. The question is a valid one for art historians to ask, and is titillating or amusing to many viewers. But with many of her flower paintings, such as Oriental Poppies, it is a stretch to relate them to female anatomy.

In the context of her whole body of work, the flowers celebrate the beauty of the natural world simplified into shapes and color. As mentioned in the previous post about outdoor art, a large scale allows us to see objects in a new way. O’Keeffe’s flowers encourage us to look more carefully at the colors, shapes, and delicate structures of every flower we see.

Even so, many people consider O’Keeffe to be a powerful figure in feminism through art in two ways. First, visual references to women’s most intimate parts displace traditional (meaning masculine) subjects and aesthetics. Second, O’Keeffe’s commercial success showed that not only men were capable artists. O’Keeffe inspired women artists with her work and her confident and independent personality. But she did not want to be associated with feminism. She wanted to be respected as an artist, not as a woman artist. She said “The men liked to put me down as the best woman painter. I think I’m one of the best painters.”

In 1929 O’Keeffe visited New Mexico with an artist friend. For the next twenty years, she spent most summers there, then moved there permanently. Don’t miss our next post, Georgia O’Keeffe in New Mexico.

I have always appreciated the vibrancy of her work. I particularly gained insight from the “zooming in” comparison of the Red Canna flowers. Thanks for this informative piece! Looking forward to reading part 2.