Mary Cassatt stands out among the Impressionists in two ways. She was an American, and she was a woman. She was born near Pittsburgh in 1844, the daughter of a wealthy banker. Her family moved to Philadelphia where she started school. She lived in Europe for five years as part of her education. There she learned German and French, took music and drawing lessons, and was exposed to the work of artists like Ingres and Delacroix who were in vogue before the Impressionists emerged. She also saw works by artists like Degas and Pissarro who would become colleagues in her adult life.

Even though her parents did not want Mary to become a professional artist, they sent her to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts when she was 15. Art school was thought to give young ladies social skills they would use as they took their places in polite society. Even so, only about 20% of art students were female. Mary wanted to be an artist, but found the pace of classes to be slow, and the attitudes of male teachers and students to be condescending. Even the program itself treated female students differently. While male students drew from live models, female students had to refer to statues.

Mary left the Academy and convinced her father to let her move to Paris in 1866 when she was 22, accompanied by her mother and family friends. In those days (surprise, surprise), the Ecole des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts) did not admit women, so Mary had to take private lessons to continue her art studies. Fortunately, she had prominent teachers. She also spent a lot of time copying paintings in the Louvre.

Within two years of arriving in Paris, her painting A Mandolin Player was accepted by the jury for display in the Paris Salon. The Salon was a prestigious biennial exhibition that was almost the only way for an artist’s talent to be validated and presented to a large audience.

The Impressionist movement began to weaken the salon system by mounting its own shows. But Mary stayed within the system for years. In 1870 she moved back to the U.S. and lived with her parents. Although her father paid her living expenses, he would not pay for art supplies. Unable to sell her paintings and with little opportunity to study the works of others, Mary almost gave up on art. She thought of moving west and getting a job.

A Pittsburgh bishop liked her work and commissioned two paintings, copies of works in Parma, Italy. With her advance, she returned to Europe, which was for her the seat of the art world. Things started looking up for her. She entered Two Women Throwing Flowers during Carnival in the 1872 Salon, and sold it. She was also a hit in Parma. In 1874 she moved to Paris, joined by her sister.

The salon system began to grate on her. Its juries were conservative, not looking for innovation, and they often snubbed women artists. Mary was outspoken and unwilling to try to win over jurors. In 1877, when her entries were rejected by the Salon, her mentor Edgar Degas invited her to show with the Impressionists, the radical painters who were despised by the art establishment. But their work started to appeal to collectors who valued a new approach to painting. Their 1879 exhibition was a success. Mary showed 11 paintings including a masterwork titled Lydia in a Loge, Wearing a Necklace. Over time, Mary promoted Impressionists among American collectors.

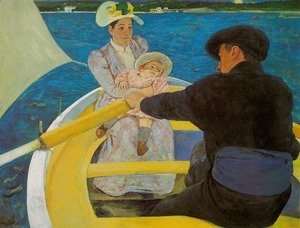

Mary was always advocating for her rights, and for all women. She was an independent woman who created a space for herself in the art world dominated by men. In the 1910s, back in America, she spoke for women’s right to vote, even when it cost her. Her own sister-in-law led boycotts of her 1915 Philadelphia show. Mary had planned to give or bequeath paintings to her heirs, but in reaction to the boycott, she sold some off, like The Boating Party bought by the National Gallery. Not bad!

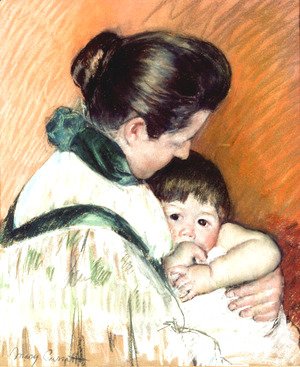

Although Mary did not want to be known as a woman artist, the subjects in her later paintings were often women. And even though many of the beautiful scenes depict women in traditional roles, she gave them dignity. Some of her most beloved paintings are scenes of mother and child that show us the tenderness, strength, and sacredness of their bond. The most well-known painting is The Child’s Bath. Perhaps in a future article we can study several of Mary’s paintings in detail, but today let’s celebrate motherhood.

Take a look at our 2021 Mother’s Day post, 4 Memorable Artworks about Mothers