When an artist wants to create a realistic image of objects in space (their placement in relation to each other), she is challenged to create the illusion of three dimensions on a two-dimensional surface, like a canvas. We are accustomed to using a camera to do this automatically. As realistic as photos are, they don’t capture objects completely because they lose the third dimension of depth. If you have only seen photos of a celebrity, then see him in person from the front and the side, he will look different from what you expected. And when taking a scenic photo, sometimes a breathtaking view looks blah in its digital image. The reverse can also happen, the photo looking better than the real scene.

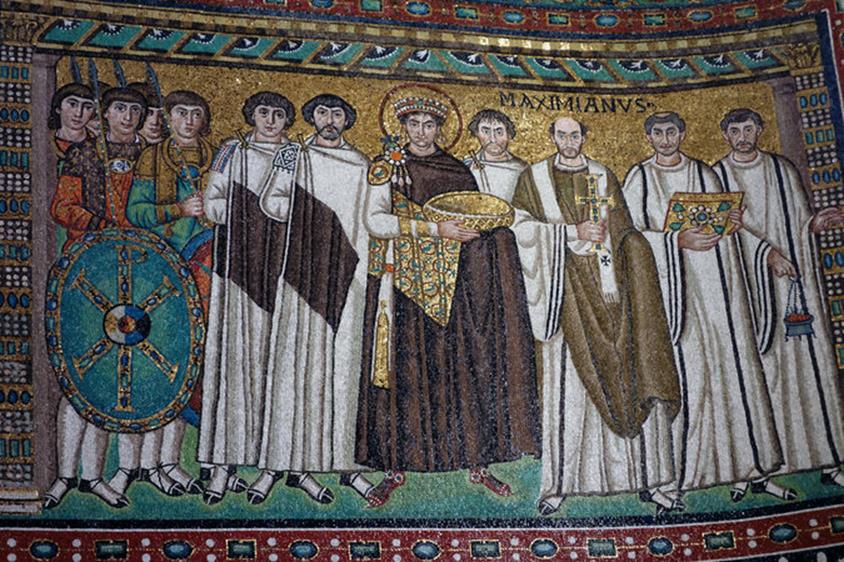

Now imagine creating art before the camera was invented, before anyone could easily turn three dimensions into two. In earlier periods, artists either didn’t value creating the illusion of depth, or they didn’t know how. In Byzantine art, figures are placed across the front without putting them in an architectural setting, such as a room, or an outdoor setting.

Photo: Steven Zucker, CC: BY-NC-SA 2.0 They look flat, like paper dolls. Even when one figure stands in front of another, they look bunched up as if all are standing in the same space, all facing forward, and with no sense of movement. Yet, the flatness takes nothing away from the beauty of this mosaic.

But, in general, people consider realism the measure of an artist’s skill. Pretend we are back in first grade. The teacher asks the class to draw a cat, with the best drawing to be displayed on the bulletin board. A stick figure would lose to a drawing that shows volume. And if we produced a cat that Picasso might have drawn, or we produced a Rothko-like color plane to express the essence of a cat, not only would we not win 1st prize, we might get sent to the principal’s office. The “best” drawing will be the one that looks most like a real cat.

Artists grappled with how to create more realistic scenes. They experimented with ways to suggest space and distance with only two dimensions; we call this method perspective. One of my favorite artists is Giotto, who painted frescoes and panels in Italy in the early 1300’s. Here is his Lamentation, a fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua that depicts mourning after Jesus was removed from the cross.  I love Giotto’s work because the scenes and figures are simple, yet they show his pioneering efforts to create the illusion of space, to place the viewer in the scene, and to present people more realistically than the Byzantines did. Figures are placed in relation to each other. Their clothing hangs more naturally, and their faces show emotion. The figures in the sky are not rosy-cheeked cherubs; instead we see grief-stricken angels.

I love Giotto’s work because the scenes and figures are simple, yet they show his pioneering efforts to create the illusion of space, to place the viewer in the scene, and to present people more realistically than the Byzantines did. Figures are placed in relation to each other. Their clothing hangs more naturally, and their faces show emotion. The figures in the sky are not rosy-cheeked cherubs; instead we see grief-stricken angels.

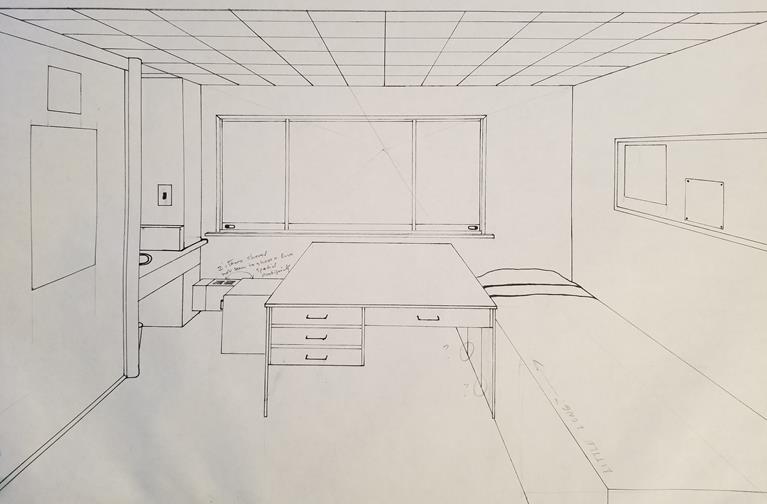

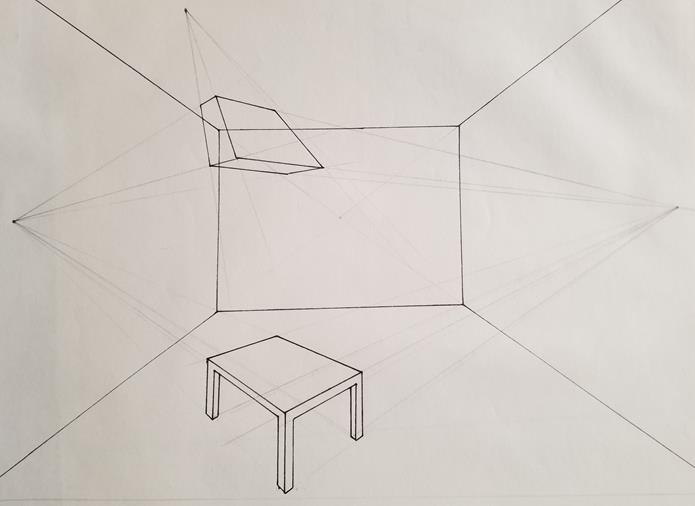

Experiments in perspective evolved into a mechanical approach. A common studio art class assignment is to create a perspective drawing of a room. You can start by drawing the back wall, let’s say a simple rectangle. Then pick a vanishing point on the horizon, the point on which parallel lines that express depth (that move away from you) will converge. As you draw the two side walls, the ceiling, and the floor, you place those lines so that, if they extended beyond the back wall, they would meet at the vanishing point. Other objects you place in the room, like a table, also follow that rule. Here is a perspective drawing I did of my dorm room.  This can get more complicated because you can use more than one vanishing point, as shown in my second drawing.

This can get more complicated because you can use more than one vanishing point, as shown in my second drawing.

Using perspective in a drawing might seem like a visual trick, but it reflects the reality of how we see. Try this now. Stand in a hallway and look at a side wall. The portion of the wall near you looks higher than the far end of that wall. Now look at the line at the intersection of the wall and the floor. As you follow that line from you to the end of the hall, it appears to rise and to move toward the center. The line at the intersection of wall and ceiling appears to drop. If we could extend those lines, they would converge on a vanishing point. We know the dimensions of the hall are the same at both ends. But our brains process the visual information so that we take the distortions not as reality, but as cues about distance and the relative sizes of objects. If we see two identical objects, we assume the one that looks bigger is closer to us.

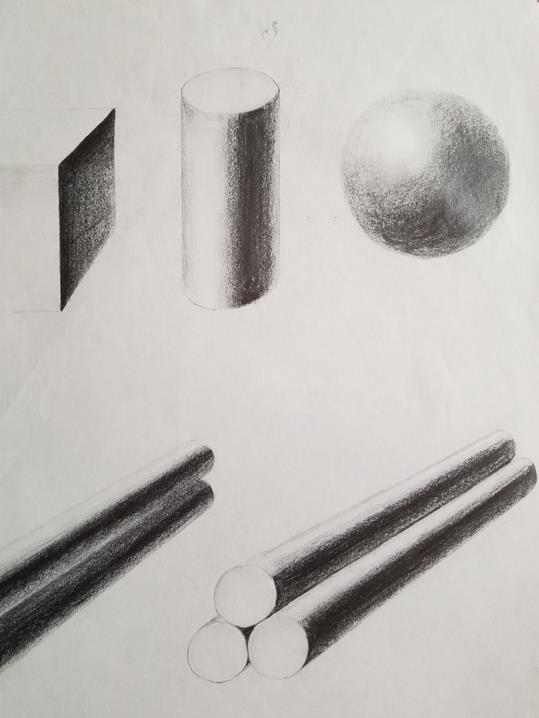

Shading can also be used to make a three dimensional object look more realistic when we draw it in two dimensions. By going from light to dark values we can give a circle the volume of a sphere. Here is another of my drawing exercises.

We’ve seen how artists can use perspective and other tools to make their drawings more realistic, more believable. I’ll apply a quote by Salman Rushdie to drawing: “Reality is a question of perspective.”

Follow us on Twitter @artanddesign101 so you don’t miss fun news like Wednesday’s post about the bowl bought at a yard sale last year for $35 and sold this week for $721,800.

This is perfect for an art neophyte like me! While I value art and artists, I have not studied art appreciation. Enjoyed the clear explanation and examples, especially the Byzantine Art vs. Giotto example. I look forward to learning more through your blog!