Today’s post moves us from visual art to design as expressed in architecture.

In 1991, the American Institute of Architects named Frank Lloyd Wright the greatest American architect of all time. In 2019, UNESCO added eight of his buildings to the list of World Heritage Sites. He gave us iconic homes, churches, office buildings, and even a museum. Here is a look at his residential projects that gave America its first architectural style.

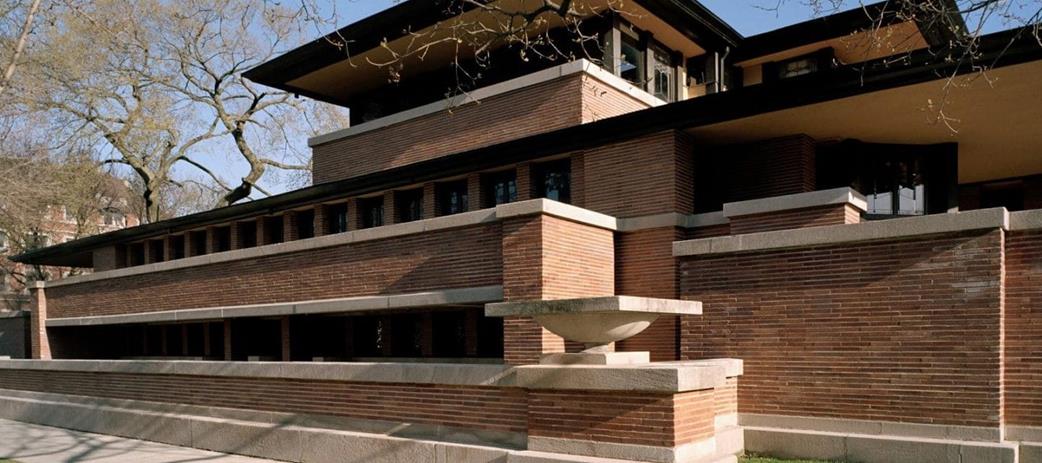

Robie House

When I visited the Robie House, I rode a city bus from downtown Chicago to the Hyde Park area. The seven block walk from the bus stop made me aware that I was visiting a real house built in a real neighborhood, not a tourist attraction. The house was built for Frederick and Lora Robie in 1910, kicking off what became known as the Prairie style of house design.

Before this, designs like Colonial, Victorian, and Tudor borrowed from England. Wright flipped the English emphasis on verticals to horizontals, using a huge cantilevered roof. The home’s entrance is hidden on a side. Once in the door, I walked up steps, landing in an open living and dining space. Light through art glass windows filled the space, but the design kept it out of view of passersby. Art glass doors opened onto a porch shaded by the cantilevered roof. Wright designed everything from window patterns to tapestries, cabinets, and gates. The original plan was to have the house completely filled with furniture designed by Wright, but financial difficulties caused the Robies to sell the house after fourteen months. The house was almost demolished in 1957. Wright intervened, saving the house; it is now a National Historic Landmark.

When you visit Robie, cross the street and walk a block north to see the huge Rockefeller Memorial Chapel built in Gothic Revival style in 1928.

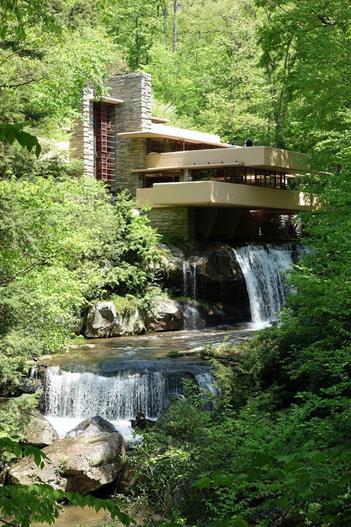

Fallingwater

In 1935, Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann commissioned Wright to build a summer home in Mill Run, Pennsylvania, on a lot that featured a stream. Wright believed a house should look like it grew from its site, rather than plopped onto a lot. So instead of building the home with a view of the stream’s waterfall, Wright designed the house “to live with the waterfall.”

He anchored reinforced concrete to existing rock and built cantilevered terraces above the stream. A suspended staircase takes you from the living room down to the stream. As in the Robie House, the floor plan is open and walls of glass connect the interior space to the natural space outside. In 1963 the owners donated the house and the surrounding 1,543 acres to a nonprofit that protects exceptional natural places. Fallingwater became a museum the following year.

Western U.S.

Wright built a number of houses in the West including the Ennis, Freeman, Hollyhock, and Storer Houses in Los Angeles; the Hanna House in Stanford CA; the Friedman House near Pecos, New Mexico; and the Price House in Paradise Valley, Arizona.

A great place to see Wright’s work is Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona. It was built in 1937 as an experimental, desert version of Taliesin, his home in Wisconsin. He designed the buildings and all the furnishings, using local materials to integrate the complex of buildings with the surrounding landscape. Besides his living and office spaces, he included a studio, a workshop, theaters, and places for apprentices and staff to stay.

A Stay at a Wright

You can get a feel for Wright’s work by taking a tour of a Wright house. But if you’d like to get a sense of living in a Wright property, you can stay at the Arizona Biltmore in Phoenix. Although the resort was designed by Albert McArthur, Wright provided on-site consulting. At times he took credit for the place, then wrote that all the credit belonged to McArthur. Whatever Wright’s involvement, there is no question that when the place was built in 1929, it showcased Wright’s vision. The walls are made of blocks that were made onsite in thirty-four carved designs. The blocks give the buildings solidity and a timeless quality. Somehow the buildings feel like they belong on the property, which is remarkable given their huge scale.

I recall spaciousness, from my guestroom to the grand lobby to the multiple buildings on meticulously landscaped grounds. Everywhere there were Wright-inspired details: stained glass windows, light fixtures, and rugs.

The architectural space made for a memorable meal at The Orangerie, a restaurant originally used as a solarium. The restaurant has changed since I was there and is now named “Wright’s.” (And the practice of presenting each lady a red rose at the end of the meal was replaced by a platter of cotton candy for the table. What?)

The resort has an interesting history. William Wrigley took over the hotel in 1930. A bartender invented the Tequila Sunrise there. Marilyn Monroe sunbathed at the Catalina pool, where Irving Berlin wrote “White Christmas.” Ronald and Nancy Reagan honeymooned at the Biltmore in 1952. Every U.S. president from Hoover to Obama has stayed there. The resort is pricey with rooms and suites going from $518 to $1,278 a night in December. You can save $100 to $274 a night if you stay in the off season, but the pool will feel like a hot tub.

Today we focused on Wright’s contributions to American home design. In a future post, we will look at significant commercial and civic buildings including Unity Temple and the Guggenheim Museum. We will also learn more about the eccentric man.