When we think of works of art, we usually picture an oil painting in a frame hung on a wall. So let’s learn about some of the common materials and methods used to create and present oil paintings.

The surface is often a canvas, a piece of cloth stretched across and nailed to a wooden frame. The cloth can be smooth or nubby. In earlier times, artists often assembled their own canvases. The canvas is primed to make it less absorbent, and may be underpainted with a layer of color. Underpainting in blue can give the whole painting coolness whereas yellow can create warmness. Nowadays, we can go to an arts and crafts store and buy readymade primed canvases and even canvas boards. And if you want to paint something on a black background, you can buy a black canvas, eliminating painting the background.

Sometimes artists, including Monet and Picasso, could barely afford bread, so they surely didn’t have money for canvases. That explains why sometimes they would paint over a previous painting, or on the reverse side.

It has become common for museums to x-ray their paintings to see if something lies underneath the surface. I recall a painting that had vanished from the public eye and was assumed to be lost forever…until an x-ray of another painting found it had been painted over. X-rays can also show when the painter changed her mind, let’s say by removing a figure, or changing a gesture.  X-rays of Picasso’s “Old Guitarist” revealed a woman and child and another woman beneath the man that we see. But I have mixed feelings about museums showing what an artist covered over. Part of me feels that we should respect the artist’s choices; that looking for painted-over items is like looking through someone’s trash. But I recognize that x-ray and infrared findings can have art-historical value, adding to our understanding of an artist’s approach. And in one case, they solved the mystery of a lost painting.

X-rays of Picasso’s “Old Guitarist” revealed a woman and child and another woman beneath the man that we see. But I have mixed feelings about museums showing what an artist covered over. Part of me feels that we should respect the artist’s choices; that looking for painted-over items is like looking through someone’s trash. But I recognize that x-ray and infrared findings can have art-historical value, adding to our understanding of an artist’s approach. And in one case, they solved the mystery of a lost painting.

Oil paints are made of linseed oil from flax and powdered pigments mixed into a paste. Pigments came from earth, minerals, plants and poisons, insects and shellfish, urine from cows that ate only mango leaves, and even Egyptian mummies. Ultramarine blue came from lapis lazuli, a semi-precious stone mined in Afghanistan. These valuable ingredients from faraway places made some oil paints very expensive, especially to a starving artist. Lab analysis of paints can help a historian determine the age of an oil painting by matching the ingredients to the period in which they were used. Some of the pigments were toxic, such as white that was made from lead and emerald green that contained arsenic. Exposure to these toxins while painting and making paints could poison artists, causing brain damage and even death; truly, some painters sacrificed everything for their art.

Currently, and fortunately, oil paints are largely synthetic, but some are still expensive. At Dick Blick’s, a 1 ½ oz. tube of Grumbacher’s Burnt Sienna costs $6.29 but Cobalt Blue Deep costs $18.89.

Currently, and fortunately, oil paints are largely synthetic, but some are still expensive. At Dick Blick’s, a 1 ½ oz. tube of Grumbacher’s Burnt Sienna costs $6.29 but Cobalt Blue Deep costs $18.89.

Oil paints can be thinned with turpentine. They are translucent, allowing light to move through the layers, which can give effects of depth or light. They take a long time to dry, anywhere from two to twelve days, depending on the colors and thickness of layers, allowing time to blend and layer colors and to change what has been painted. By comparison, acrylic paints, widely used since the 1960s, dry in about 20 minutes, so the painter has to work quickly.

In earlier times, after a painting was done, the canvas would be varnished. Just like on a piece of wooden furniture, varnish was used to seal and protect the paints and to make the surface glossy. Viewers valued a surface that was perfectly smooth with no signs of the artist’s brushstrokes. As a painting ages, the colors darken; much of that is due to the varnish. So, removing aged varnish is often the most significant step in restoring an oil painting.

In more recent times, varnish and smooth surfaces were eliminated, sometimes in favor of thick buildups of paint in a technique called impasto to add texture; similarly, a nubby, rough canvas also adds a dimension to the painting. Brushstrokes are often visible, leading us to imagine the act of painting, not just the result.

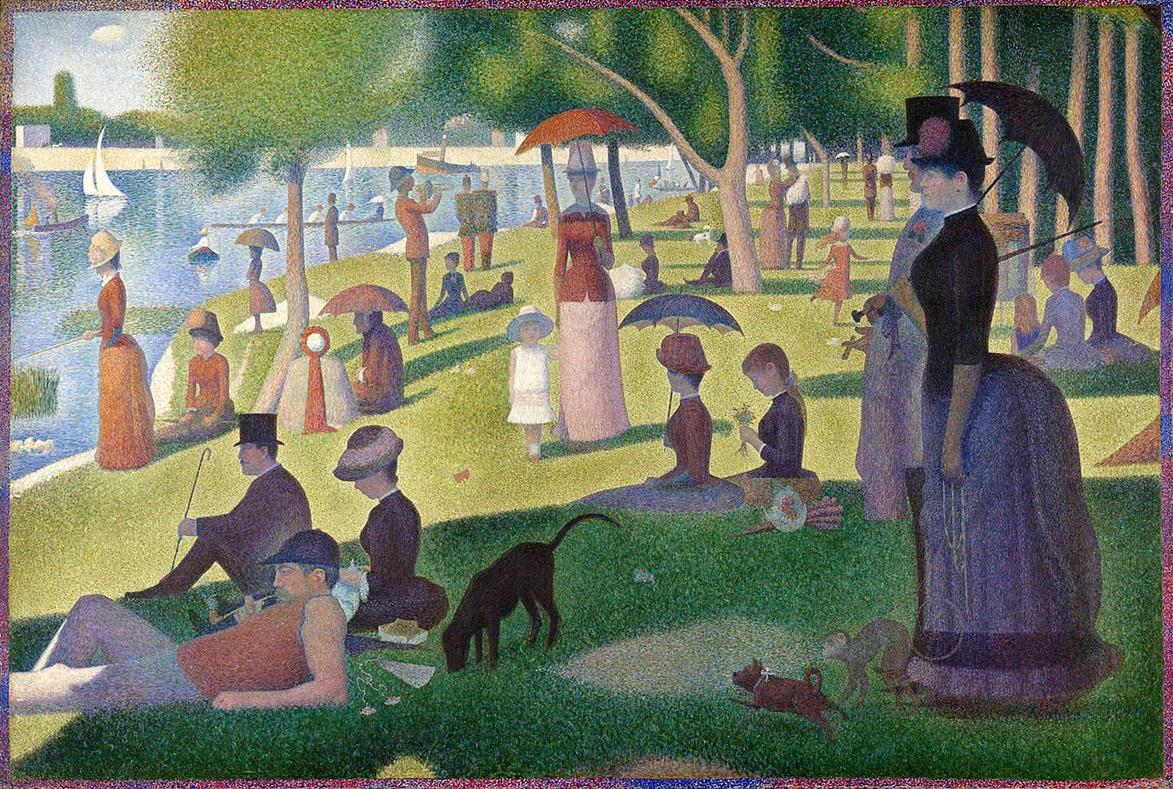

Frames affect how we perceive a painting. Ornate carved wooden frames give a painting formality, suggesting the seriousness of the work, and linking it to historical periods when the frame was considered an integral part of the painting. On the other hand, slim metal frames suggest the modernity of an artwork. One artist always framed his work on the canvas. Look closely at this iconic pointillist painting by Georges Seurat, “Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.” Notice how the scene is surrounded by a border, also painted in pointillist style. Seurat himself put the painting in a simple white frame.  When people have an artwork framed online or at a local arts and crafts store, they usually choose a frame, a mat or two, and a sheet of glass. Notice that in a museum, however, mats and glass are rarely used. Although glass would protect a painting, museums don’t glaze because glare and reflection make the artworks harder to see and photograph. And since the purpose of a mat is to create space to keep the glass from touching the painting, there is no need for mats if there is no glass.

When people have an artwork framed online or at a local arts and crafts store, they usually choose a frame, a mat or two, and a sheet of glass. Notice that in a museum, however, mats and glass are rarely used. Although glass would protect a painting, museums don’t glaze because glare and reflection make the artworks harder to see and photograph. And since the purpose of a mat is to create space to keep the glass from touching the painting, there is no need for mats if there is no glass.

Follow us on Twitter @ArtandDesign101. Tuesday’s tweet got Likes from The Metropolitan Museum of Art and 1st Dibs (a luxury interior design and art marketplace) in New York City, and from art lovers in Canada and Australia.